The cardinal electors, by the numbers

The data on the men who will choose the pope

Of the 135 eligible cardinal electors in the Church today, 133 are expected to enter the Sistine Chapel in early May to elect a new pope, while two have said they are unlikely to attend due to illness.

But who are those men, and how will this conclave be different — and similar — to those which have come before?

The Pillar looks at the numbers.

—

With 135 eligible cardinals — and almost all expected to attend — the 2025 election will be the largest conclave held in modern Church history.

Before Pope St. John XXIII, who expanded it in 1958, the size of the College of Cardinals had been set at 70 members since the 16th century.

Seventy was an upper limit, but there were not always 70 cardinals in the college. In the centuries before John XXIII, appointments to the college came only when a number of cardinals had died, so that the pope would appoint more, to bring the number back up to (or near) 70.

That practice sometimes led to small consistories, and at times more than one consistory in a year. For instance, in 1927 the number of cardinals fell to 67, and so Pope Pius XI held a consistory on June 20, appointing two additional cardinals, bringing the total to 69.

But when six additional cardinals died in the second half of the year, the pope held a second consistory and appointed five more.

At other times, global events prevented the appointment of more cardinals, and so the numbers in the College fell to much lower levels. The lowest point in modern Church history was during World War II.

When Pope Pius XI held the final consistory of his pontificate in December 1937, he brought the number of cardinals up to 70. But because of the death of Pius XI in February 1939, and the outbreak of war in Europe six months after the election of Pius XII, another consistory was not held until 1946.

By the time Pius XII called that first post-war consistory in 1946, the number of cardinals had fallen to 38. Pius brought it back up to strength with one of the largest consistories up to that time, appointing 32 new cardinals and bringing the total back up to 70.

Because of the custom of never exceeding 70 cardinals at a time, pre-Vatican II conclaves tended to be less than half the size of the one the Church is about to experience.

It was in 1958 that Pope John XXIII expanded the College of Cardinals beyond 70. And in 1975, Pope St. Paul VI set the current target size of 120 cardinal electors.

Popes since that time have treated 120 as more of a target than a hard limit. Popes have often appointed enough cardinals to bring the number of electors above 120, expecting it to fall back down below 120 within a year or two as cardinals pass 80, the maximum age for voting.

That maximum voting age is also the result of fairly recent Church law. Pope Paul VI created the distinction between voting and non-voting cardinals in 1971, decreeing that cardinals who had reached the age of 80 were no longer eligible to vote in a conclave.

The result is that while cardinals continue to live longer as a result of advances in medical technology, the cardinals voting in recent conclaves have actually been slightly younger than those who elected Popes John XXIII and Paul VI, before the age rule.

Indeed, the eligible electors for the 2025 conclave are slightly younger, on average, than those of 2005 and 2015, though slightly older than the two conclaves in 1978.

That fact is because of Francis’ less standard approach to picking cardinals during his pontificate.

While the youngest cardinal in the 2013 conclave was Cardinal Baselios Thottunkal, 53 years old at the time, there will be in this year’s conclave five cardinals younger than Cardinal Thottunkal was in 2013, including Cardinal Mykola Bychok, who is 45.

The last time a man that young was made a cardinal was in 1973, when Paul VI named Archbishop Antonio Ribeiro, the 44-year-old Patriarch of Lisbon, a cardinal.

Such young cardinals were once more common, when life expectancy was shorter than it is now. Pope Leo XIII made eight cardinals who were 45 or younger, including one who was just 37 at the time he received the red hat. But the youngest man made cardinal by Pope Benedict XVI was 53, and the youngest one appointed by Pope St. John Paul II was 47.

Of course, another key difference often discussed in regard to the cardinals appointed by Francis is their geographical dispersion, “to the peripheries.”

According to the birth countries of eligible cardinal electors in 2025, the biggest single change from previous conclaves is that there are significantly fewer Italians.

Before World War II, the College of Cardinals was more than 50% Italian. That changed after the war, as more cardinals from across Europe and the rest of the world were named.

During the 1978 conclaves — and right up until the 2013 conclave which elected Pope Francis — the college was still about one quarter Italian by birth. But in the 2025 conclave, only 14% of the eligible voting cardinals are from Italy.

The biggest gainers are Asia and the Pacific, which increased their share of the college from 10% to 16%. There are now more voting cardinals from the Asia and Pacific region than there are from Italy.

Representation also increased for the Africa & Middle East region, and for Latin America, both of which now equal or exceed Italy in representation.

Like Italy, North America has decreased share in conclave representation, falling from 12% of eligible electors at the 2013 conclave to 9% of the 2025 election.

The rest of Europe, aside from Italy, slightly increased its share.

Although Italy and the U.S. will both have fewer native sons in the 2025 conclave than in previous ones, they still remain the two countries with the largest number of native cardinals.

There will be 19 men born in Italy eligible to participate in this conclave, down from 28 in 2023, and nine born in the U.S., down from 11.

The country with the next largest eligible representation is Brazil with eight, up from 5, followed by Spain with seven, up from five — although one Spanish cardinal has indicated he likely will not participate.

—

As the make-up of the cardinal electors changes, one factor remains fairly constant: the percentage of voting age cardinals who are members of the curia rather than current or retired diocesan bishops.

The 2013 conclave had an unusually high percentage of curial cardinals at 27%. But the 20% representation for the curia in the 2025 conclave is virtually identical to that in the 2005 and 1978 conclaves.

What has clearly changed, however, is where the cardinal members of the curia come from.

While the curia used to be heavily Italian, with only 14% of current voting-age cardinals coming from Italy — and many of those being in geographical sees throughout the country — many of the cardinals who are working full time in the curia were born in other parts of the world.

Of course, all the discussion of how Pope Francis has shaped the College of Cardinals that will choose his successor brings up the obvious question: To what extent is this a “Francis” college now?

The answer is that the vast majority of the cardinals who will vote to pick Francis’ successor will be men elevated to the college by Francis himself — but they are hardly an unusual percentage from a historical point of view.

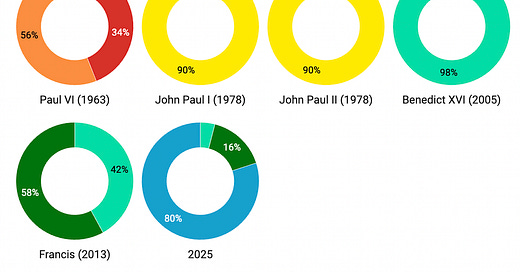

Eighty percent of the cardinals eligible to vote in the 2025 conclave were chosen by Pope Francis.

That’s certainly more influence than Benedict XVI had over his successor. In the 2013 conclave 58% of the voting-age cardinals had been appointed by Benedict XVI while the other 42% had been appointed by John Paul II.

After John Paul II’s long pontificate, 98% of the cardinals voting in 2005 had been appointed by John Paul II.

But interestingly, after Paul VI’s 15-year papacy, 90% of the cardinal electors voting in the two conclaves of 1978 had been appointed by him.

So while Francis — through his choices for the College of Cardinals — will have more of an impact on the conclave choosing his successor than John XXIII or Benedict XVI had on their successors, he will have had less of an influence than Paul VI or John Paul II.

John Paul II and Francis himself were both seen as significant departures from the men who had appointed the cardinals electing them. Similarly, it is hard to predict, based only on the fact that Francis appointed them, what the cardinals chosen by Francis will look for in a pope.

Still, this will be the largest and most widely assorted conclave in Church history.

Many of them will be men who do not know each other well, since they are normally seeing to the needs of their churches around the world’s “peripheries".

The 20% of cardinal electors who work in the curia, and others who travel often from their dioceses to Rome, may form a core of cardinals who know each other better, and that may form an important core in discussions among the cardinals.

But in other ways, the composition of this conclave may be particularly set up to generate surprises.

From the “pope of surprises,” that’s no surprise at all!

Brendan's By The Numbers columns are one of the main reasons I subscribe! Dear MSM reporters who will be cribbing from this data analysis to flesh out your conclave stories in the coming days... please at least link to the original article? And consider subscribing :)

Great analysis!

I only wish you had gone back a little bit further. In the 12th and 13th centuries there were only 12-15 Cardinals! And in the early 14th the limit was set at 20. Yep, 20.

And it stayed at 20 (later 24) for centuries until in the early 1500s Leo X added THIRTY ONE. And then Paul IV set it at 70.

The article kind of gives the impression that the status quo before Vatican II was perpetual and that the expansion was unprecedented. The College packing of the 16th century was far more expansive and unprecedented (more than doubling the size overnight).